Silenced, no more

In conversation with Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar, translator of Manoj Rupda’s Hindi novel ‘Kaale Adhyaay’ (I Named My Sister Silence)

The thing is: the boy had changed by the time he walked out of the forest. He was a human only in his body, his mind had turned as devoid of thought as that of an animal.

A young Adivasi boy is fascinated by a giant elephant he sees in his village, Basamura. To him, it seems unconquerable; its sheer size defied defeat. As if by an unknown force, he gravitates towards it, following the trajectory its mahout takes deep into the forest. Finding himself followed by a boy, the gobsmacked mahout asks about the boy’s whereabouts. The night was falling. Nothing could’ve been done except to allow the boy to tread along. The mahout makes the boy sit on the elephant’s back. “It was the first time I had climbed atop a moving object,” the boy notes. But he wasn’t done being surprised by nature; he was yet to witness a harrowing act, that of the elephant being reduced to bones by wild dogs.

Rarely does one get to witness an incident as traumatic as this young Adivasi boy does in Manoj Rupda’s Hindi novel Kaale Adhyaay (Bharatiya Jnanpith, 2015) in literature. The book takes a significant departure from here. From the forest, one moves to his home, where he’s faced by the worrisome family and his as-cool-as-ice half-sister. The boy had changed. It’s unimportant if anyone notices it. The incident would continue to define his life, but he was faced with something more pressing and urgent: his sister had left.

Point is: she wasn’t lost, she hadn’t gone missing. My sister had left. She hadn’t left any message for me. She had just left. Just like that. Just the way that mahout had left me, alone, in the forest, sitting atop the elephant ten years ago.

His sister, the one whom he would name Khamoshi, silence. Or Junoon, passion. Gone without a trace. One shocking—for a young adult—event after the other propels this narrative forward, creating an urgency for the reader to stay put until they happen to satisfy their curiosity about how he ends up in life.

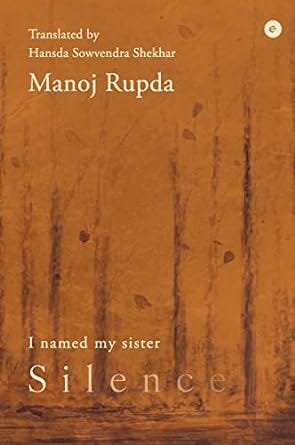

Immensely engaging, deeply moving, and astutely written, Kaale Adhyaay is translated from the Hindi by Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar as I Named My Sister Silence (Eka, an imprint of Westland, 2023). In 2023, it was shortlisted for the JCB Prize for Literature.

A recipient of the Sahitya Akademi Yuva Puraskar (for his debut novel The Mysterious Ailment of Rupi Baskey [Aleph, 2014]), Shekhar, who was shortlisted for the JCB Prize for Literature for his novel My Father’s Garden (Speaking Tiger, 2018), translates from Santali, Hindi, and Bengali to English. In an email conversation with Writerly Life, he discusses about translating I Named My Sister Silence. Edited excerpts:

When did you first read Kaale Adhyaay by Manoj Rupda, and if you could summarise how did it impact you?

I first read Kaale Adhyaay in mid-2022 when I had just finished translating Manoj Rupda’s Hindi story, Tower of Silence, into English. (The Hindi original was titled Tower of Silence, and was published in the April 2006 issue of Vagarth magazine, while the translation—again titled Tower of Silence—was published in The Dalhousie Review). To summarise the impact Kaale Adhyaay had on me: Just two chapters into the novel and I knew that I had to translate it.

In an interview with Writerly Life, J. Devika noted that a translator’s reading of a particular text is “a certain reading”—what they make out of it. I was wondering if you could share more about your reading of the book, and, particularly ‘the elephant part’ that compelled you to translate this work?

J. Devika’s answers were insightful and wise and I share the same thought as her; that a translator’s reading of a particular text is “a certain reading”. Every reader’s interpretation of a work may be different from that of others.

Regarding what compelled me to translate Kaale Adhyaay: It is a powerful work. The elephant part is just one part of its charm. There is this touching, unforgettable description of the narrator’s relationship with his elder half-sister. Had I not translated Kaale Adhyaay into English, I think I would have lost something important.

I have been informed that the eight-sentence prologue—perhaps one of the shortest and most impactful ones I’ve read—wasn’t in the Hindi version. Could you share how in reimagining this work in English you felt the need to have this prologue in place? Additionally, as you transformed the title to centralise focus on a critical aspect of Kaale Adhyaay, could you highlight the sort of challenges translators are faced with when working on rendering a work in another language? What sort of negotiations are involved here, and the risks that such creative approaches can present?

Prologue

It hurts differently to watch something immense and majestic fall lifelessly to its knees and be taken apart by powers beyond its control.

Like a ship being dismantled by cutting machines and cranes.

Like an elephant being eaten alive by wild dogs.

Like a forest being mined and ravaged by corporates.

It hurts much the same way to be left alone.

By a mentor.

By a co-traveller.

By one’s own sister.

(Taken verbatim from the book; used with permission from the translator)

Yes, the prologue was my invention. It wasn’t there in Kaale Adhyaay. I put the prologue in place to contextualise what the novel was about. Apart from being a story of a sister-brother relationship, it was also about destruction—of an animal, of a ship, of an economy, of a people. The prologue was just a hint of what a reader would find in the novel, something like a précis.

Regarding challenges: The first challenge I faced while translating Kaale Adhyaay was on which aspects of the novel to focus on and how to streamline the various things that Mr. Rupda writes about. In fact, my decision to have the title I Named My Sister Silence, too, was my way of facing that challenge. Mr. Rupda writes about the dark chapters of history—Dark Chapters would be a literal translation of the title, Kaale Adhyaay—but I somehow decided to focus on the relationship between the narrator and his sister, Madavi Irma. Also, I wanted to be sure that the novel was faithful to Koitur life as the narrator and his family were Koitur. In that, I was helped by Rozy Gawde, who comes from the Koitur community, and lives in Bastar. She was the first reader of I Named My Sister Silence and helped me with Gondi words and she basically signalled to me that yes, the manuscript of I Named My Sister Silence was ready to go out into the world.

Regarding risks: I think that when a translator takes liberty with the original text—like how I added a prologue to the translation, something which wasn’t there in the original, and the title I gave the translation was not a literal translation of the original title—they are asked questions about their decision to do so, and then the translator has to give reasons or justify their decisions.

Could you discuss how the Adivasi landscape and language in all its complexity is reflected in the book? Furthermore, as the perception about a place or community or thing is usually formed by the information about them that is socialised, and, of course, as only the powerful get to control the narrative, I was wondering if you could meditate on what informs your decision to translate a work in Hindi, Santali, or Bengali—the languages you translate from—with a wider audience. In your view, does this act of translation become an act of protest, too?

One complexity about the Adivasi society that Mr. Rupda got right in Kaale Adhyaay was how people from the same family had chosen to follow two different streams in life because of powerful parties intervening in their life: one sibling choosing to go with the rebels, while the other one joining the police. But then Kaale Adhyaay isn’t exactly about Adivasi landscape and language. It is about the atrocities that the Adivasis have had to face in their struggle to protect their land and everything that they hold close and sacred.

Regarding what informs my decision to translate a work: It is like an instinct. I just feel it, that yes, I have to translate this work. When I chose to translate Nalini Bera’s Ananda Puraskar-winning Bengali novel, Subarnarenu Subarnarekha, it was an instinct. That novel—to use the cliché—spoke to me. For one, it is set in a region by the river Subarnarekha, the river I have grown up beside (in Moubhandar, where the Subarnarekha supplied water to the township in which I grew up) and am at present working beside (Chandil is famous for the dam on the Subranarekha). The people in Subarnarenu Subarnarekha—Mahato, Bhumij, Santal, and others—are the people I live with. In Santali, the poems (by Chinmayee Hansdah-Marandi, Suchitra Hansda, Parimal Hansda, and Rupchand Hansda) and a work of non-fiction (by Shibu Tudu), which I’ve translated into English—all, to use that cliché again, spoke to me. I may translate a work that may not speak to me, but I am sure I won’t be able to do justice to it and my half-hearted effort would be visible. I recently translated Kuzhali Manickavel’s story, Paavai—from her collection, Insects Are Just Like You And Me Except Some Of Them Have Wings—into Hindi, and it was published in Vanmali Katha magazine in their January 2024 issue, and I received feedback that the story was received warmly by readers.

The book is split into two parts—Forest and Ocean. In my view, they are excellent metaphors for the alienation that the boy—and the man he becomes—experiences wherever he has been, be it the land or water. Of course, they certainly do represent the magnitude and scale of “huge” things that will collapse in front of him, but is there a subliminal hint towards the destruction of the natural world alongside representing the almost existential quest in him to locate himself in any sort of environment, which also results in him trying to bond over trauma with others? No worries if you don’t feel that way, and disagree with this observation.

I think Mr. Rupda would be the best person to answer this question. For me, I think the narrator was an empath and a strong person.

When I asked Paul Lynch why he thought Prophet Song would end his career, his immediate response was because “it is a dark book”. By any standard, I Named My Sister Silence is one of the eeriest and most unsettling works, for it addresses reality as unapologetically as one could. Having had multiple discussions about the book with people, there was a constant mention of it being overwhelmed with dark themes, leaving me to wonder how readers measure how much dark is too dark for them. How was it for you, while reading the Hindi version? Also, perhaps it is such a compact work that it surprises people that it could cover major (in scale, size, and impact) events and yet be such a brief work. Did you, in particular, feel that way—that readers prefer a focused, singular treatment of one theme or another?

I was just in awe of how powerful Kaale Adhyaay was and how masterful Mr. Rupda’s craft is.

Could you share what you are working on next? One knows that despite your day job, you do continue to read and write. What books you are reading that you’d like others to do as well?

I am quite tired and sleepy and irritable and mostly clueless nowadays, so I am working on fixing that. I just finished writing an essay, which may be published sometime soon. I just finished reading the Hindi novel, Chidiya Bahnon Ka Bhai (Brother of Bird Sisters), by Anand Harshul, which is an amazing work of magic realism and I recommend it. I look forward to reading Crooked Seeds, the new novel by Karen Jennings, and Weasels in the Attic by Hiroko Oyamada, translated by David Boyd. The cover art of Weasels in the Attic is so guchupuchu that I can cuddle with it the whole day! A friend of mine informed me about a book I may be interested in: Meow, a novel by Sam Austen.

This interview wasn’t sponsored by anyone. If you enjoyed reading it, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Unless stated otherwise, all images belong to Saurabh Sharma.

I Named My Sister Silence was one of the best novels I read last year, so it was great to know about the behind-the-scenes decisions that were taken by the translator. Great interview!