Abua Disum, Abua Raj

In conversation with Rahul Ranjan, author of ‘The Political Life of Memory: Birsa Munda in Contemporary India’

A memory must be constructed—and reconstructed—to tell a compelling story. One’s politics of remembering, however, determines what such the story is going to be about and its requisite function.

In this sense, perhaps what’s central to any act of remembrance—or storytelling—is not who but how. One of the best candidates to explore this dichotomy is anticolonial, tribal activist Birsa Munda.

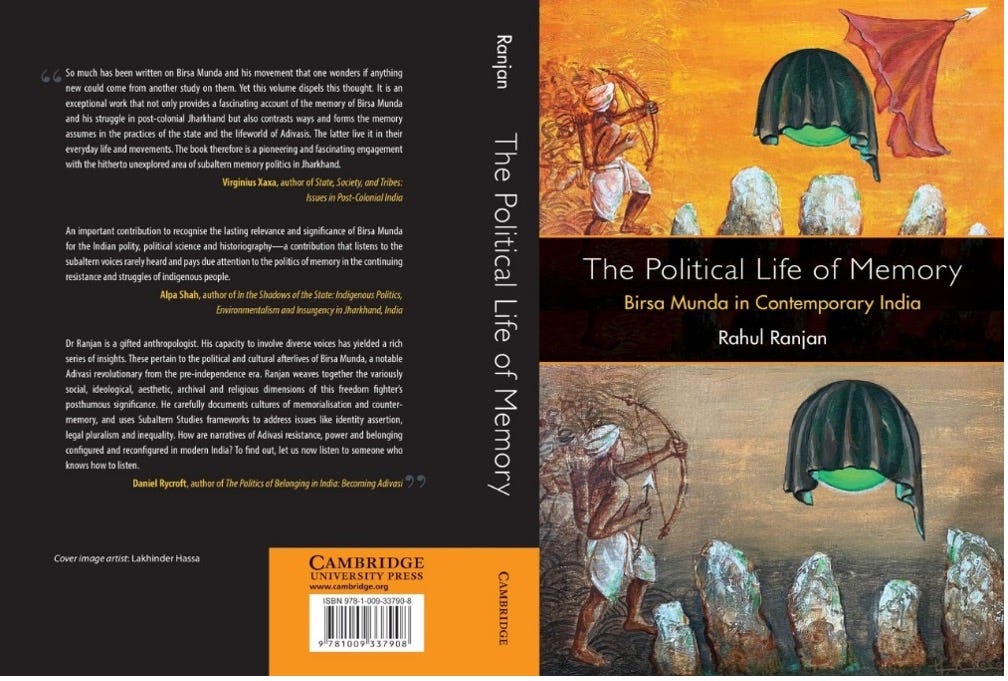

The narratives spun about and around him, as writer and Assistant Professor in Environmental and Climate Justice at the Department of Geography, School of Geosciences, University of Edinburgh (UK), Rahul Ranjan notes in his thoroughly researched and astutely written The Political Life of Memory: Birsa Munda in Contemporary India (Cambridge University Press, 2022) demonstrate why Munda happens to be such a figure.

In the Introduction to his book, Ranjan writes: “Today, however, [Munda’s] memory is evident in the form of landscape, at intersections and within cultural milieu. Political parties at the national as well as regional levels, civil societies and communities honour his memory. This makes for a widespread presence, ranging from a portrait hung in the Indian parliament (the only Adivasi leader so honoured) to statues in a tea garden in Assam and at the Ranchi airport, amongst other places.”

This makes one wonder: As everyone seem to be co-opting him, has it distorted the image that should’ve been preserved? And if not, allowing variety of stories to remain afloat, does this co-option signal a departure from the ideas Munda placed value on? Or is there a helplessness, an acceptance of sorts: that in today’s image-concerned world—for how you’re perceived or can convince others to perceive seems is the increasingly accepted currency and much else about you isn’t paid heed to, the act of memorialisation is going to be nothing but a politically motivated aesthetic exercise?

But there’s more to it. Several other questions need to be foregrounded, which Ranjan does deftly in his work that pries open the relationship between everyday identity politics, historiography and remembering, resulting in The Political Life of Memory—an immersive exploration of the contextual understanding of the Munda figure.

In an email interview, Ranjan discusses what interested him in Munda’s life, explores the connection between memory and historiography in the light of his study, and shares what can mobilise support to help bring more such works out there in the world. Edited excerpts:

It is interesting that the title of your book centralises the aspect that the impressions one makes of the past are heavily influenced by a narrative; they need not entirely be rooted in history-telling, which happens to be controlled by elites. Which is to say that subalterns were speaking—the [Gayatri Chakravorty] Spivak notion you help invert in your book, but they were either being silenced or not being heard. In this context, would you like to share what excited you to study Birsa Munda and why you felt he was a figure you wanted to closely observe and record?

Birsa Munda is a political maverick for me. Part of the 19th-century anticolonial canon, he made a clarion call against the British Raj, reinstating “Abua Disum, Abua Raj” (My Village, My Rule). The slogan has since been a rallying point for various forms of emergent movements that seek Adivasi rights. He had an incredible sense of awareness about his community—namely, the onslaught of Adivasi land and, more importantly, the shifting practices within the cultural milieu.

Growing up in Darbhanga (Bihar) and later in Ranchi (Jharkhand), his presence filled my everyday life. But I guess the impression of his memory was never tangible until I returned to Ranchi for my MPhil research at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) on land rights and social movements.

During the pilot field study, I was assured listening to various Adivasi activists who engaged in the movement that Birsa’s afterlife is glaringly present, for there is something unexplainable about his mammoth memory emerging through various narratives of those who stage clear and articulate voice of their rights.

Birsa, especially his Ulgulaan (rebellion), is often invoked as a metaphor to portray his charismatic role in staging a formidable fight against the dikus (outsiders)—the landowning class (Zamindars), British Raj. Above all, an oeuvre of scholarship produced by Adivasi scholars, including the Sangeet Natak Akademi Awardee and Padma Shri awardee Dr Ram Dayal Munda (PhD, University of Chicago), journalist, activist, and author of Angor (Adivaani, 2016) Jacinta Kerketta, and the author of The Adivasi Will Not Dance (Speaking Tiger, 2015) Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar, amongst other became a pivotal inspiration to write a PhD, which eventually became a book on Birsa Munda and his memory.

In the present dispensation, the project of memorialisation has witnessed a unique tie-up with the manufacturing of history to canvass support. As you note one of the questions you posed in the book was, How do people relate to representation of the past? I was wondering if you would like to share the findings against this question in relation to Birsa Munda and offer a comment on the contemporary phenomenon of idol worshipping almost to the point of manufacturing an identity, which is not concerned with futures but wants a particular narrative past to be accepted.

For a long time, Adivasi leaders were forcefully pushed into the abyss of historical confines, and often, they emerged only in fragments of writings. Memorialisation is a mnemonic practice; it cultivates and shapes public memory about a historical event, individual and time. In fact, until recently, universities and schools did not teach about rich Adivasi intellectual scholarship. This process enforces amnesia about the historical past and often enables misrepresentation at best.

To your point about idol worshipping, it’s not prevalent at all within Adivasi society. In fact, Adivasi believes in a formless spirit, the bongas. However, over the years, Birsa’s statues have populated the cities and are increasingly (as I discuss in the book) appropriated by political parties, including the current dispensation.

The selective curation of his memory, which is mainly ahistorical in representation, serves to gather nationalism. But Birsa’s memory is difficult to appropriate; it is an insurgent memory of rebellion—and a range of young Adivasi scholars, through their remarkable work, are showing the limits of representation.

The plundering that the Adivasi society—people and land—underwent during the colonial era perhaps isn’t markedly different from the way contemporary political movements are muzzled. As you have a contextual understanding of this subject, I was wondering if you would like to share the similarities, differences, and unique ways the exploitation, memorialisation project, and political appropriation have witnessed in the present regime compared to the colonial one.

As I argue in the book, the institutional memorialisation process in India, especially in Adivasi regions, is intimately tied to the extraction—of both resources and history. Unsurprisingly, a road is built through the deep stretch of forest in a mineral-rich area to erect a statue. Notwithstanding, built environment (statues, memorials) as a tool of public remembrance in these areas do hold symbolic value, but the question is, What does it bring to those who already have embodied knowledge about the many lives of Birsa passed down through folksongs, hymns, and stories for generations?

In terms of the memorialisation process, there is a remarkable shift. Within colonial history, Birsa’s canonisation through memorials is difficult to trace—or at least my research shows limited presence. Birsa Munda’s statue began to surface quite dramatically with the rise in the movement for granting Jharkhand statehood. Interestingly, ever since, there has been a recurring and noticeable trend in the aesthetic transformation of these statues. They are mainly inconsistent with the original portrait of Birsa (tied in chains upon the arrest).

In fact, quite contrary, there has been a political attempt at transforming his portrayal from being tied to a chain, which symbolises rebellion for Adivasi, to a more saintly or social reformer figure. Adivasi activists have powerfully confronted these attempts to register their voices and to signify that Birsa Munda is an Adivasi icon.

Canonising him as a caste Hindu leader is a historical wrong—reminding here is an exchange I had with an elderly person in Khunti, who said, “Birsa is a Munda first, Adivasi second and rest of all for what you may think of him”. Birsa’s memory and identity are inextricably tied to Adivasi’s struggle. Any attempts of appropriation cannot circumvent this reality.

The view that those who are from the outside shouldn’t be documenting an Adivasi—or by extension, any marginalised community—life is gaining currency. While there are fine examples like Australian historian Peter Stanley’s Hul! Hul! The Suppression of the Santal Rebellion in Bengal, 1855 (Bloomsbury, 2022), it is entirely possible that limited exposure to the negotiation that someone undertakes in India could potentially be problematic. For example, you note in one of the chapters that as Munda is treated as a Godlike figure, it can “typecast the entire community as Hindu, a prototype nationalist fervour at ‘assimilating’ the Adivasis in the fold.” In that context, who should be able to tell a story and why? What sort of mechanisms do you believe work in tandem to ensure the silencing of subalterns?

When I discovered the arrest letter of Birsa Munda at the British Library in London as a young PhD student, I ran off to the entrance and rang Maa to say; this is it; I found a living testament of a rebellion. The letter said, “This is to confirm the arrest of ringleader Birsa Munda and his followers.” The reason I mention this anecdote here is because my work—as a writer and or as an academic—requires ethical clarity for its pursuit. That piece of archive complimented endless narratives I carried from the field about the Birsa rebellion. It gave me a purpose to believe in my work.

I speak about people and their voices in my work; I write alongside, not on them.

These are not simply cursory tasks. It forms the basis for writing in solidarity as an outsider: non-Adivasi and upper-caste Hindu. I am aware this declaration may seem symbolic; therefore, I make citational choices in the book—by streamlining and drawing from the work of Adivasi intellectuals. I often think a lot about writing. I think more often than I actually write. I edited the book through every sentence and paragraph. As a writer, I feel responsible for my writing. Our writing creates imagination about the people, places and lives we write about.

This book is about the memory politics of an Adivasi canon, not about Adivasis. Memory is not history; it represents the past and events. I often use scaffolding as a metaphor to explain this generative tension—who am I to write on lives and people I don’t represent? The scaffolding is a careful consideration of the community’s interest that allowed me space to enter and learn from them. I am still learning; knowing how to hold these historically important and sensitive issues delicately as an ongoing process. Lastly, as Ruby Hembrom, a prolific writer and publisher, in her writing reminds us, “No outsider can own or appropriate: our stories run through the fabric of our collective life like blood made out of time, dreams, and hope.” Following Ruby’s evocation here, we should be asking what we can learn from communities. Often, words can reinforce assumed privilege as a writer and academic. I am eager to learn.

During the course of your research and documenting your work, would you like to share what sort of assumptions you had that stood challenged, what concerns you were faced with, and what possibilities the entire project helped you explore/unearth?

This is an interesting question. A lot of assumptions were shattered. I was trained in political science in India before moving to London for a PhD in Anthropology. The way courses are taught in politics, with its due merit to rigour and extensive breath of reading, also excludes or remains irreverent to writings by Adivasi scholars. Apart from Virginius Xaxa, who was occasionally assigned, I was not presented with any opportunity to read more broadly.

When I first read Dr Dayal Munda’s work on Adi-dharam (published by Adivaani, an Adivasi publication led by Ruby Hembrom) and The Jharkhand Movement: Indigenous Peoples’ Struggle for Autonomy in India, I began to learn a lot, and I also confronted my deepest fear: I may not know enough or could write on this. I spent an entire summer reading, taking notes and creating a robust review of the literature to gain strength in undertaking this mammoth project on memory.

Notably, as a writer from a privileged caste background, I also underwent an inner dialogue with my own intersectional identity—developing a composite whole for all contradictions to exist. I was very harsh and uncertain about my work during the PhD and basically devoted time between archives and the field. My supervisor, Corinne Lennox, and several very kind and generous Adivasi scholars I met in Ranchi helped me navigate the research. I guess that introspection, which remains a process—an ongoing one as I write in admission to my ethical positioning, gave me clarity. I am continually learning from my peers, friends, colleagues, and students, as I teach at Edinburgh now. We are who we are; that is our social fact. But we are also intersectional. And I wish I would have the courage to tell another, perhaps, personal story one day. But how we mobilise our privileges, negate them, and often use them for creating a more ethical work matter.

Unless stated otherwise, all images belong to Saurabh Sharma.

This interview wasn’t sponsored by anyone. If you enjoyed reading it, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

बाघ और सुगना मुंडा की बेटी - Anuj Lugun - can be added to the books mentioned. Enjoyed the interview.